Datenvisualisierung mit

Matplotlib

Als erstes: IPython interaktiv machen:

%matplotlib inline

# bei euch: %matplotlib (nur in iPython)

Um mit Matplotlib arbeiten zu können, muss die Bibliothek erst einmal importiert werden. Damit wir nicht so viel tippen müssen geben wir ihr einen kürzeren Namen:

import matplotlib as mpl

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (10, 8)

plt.rcParams['font.size'] = 16

Außerdem brauchen wir ein paar Funktion aus numpy, die euch schon bekannt sind

import numpy as np

Ein einfaches Beispiel: \(f(x)=x^2\)

x = np.linspace(0, 1) # gibt 50 Zahlen in gleichmäßigem Abstand von 0-1

plt.plot(x, x**2)

# Falls nicht interaktiv:

# plt.show()

Anderes Beispiel: \(\sin(t)\) mit verschiedenen Stilen. Vorsicht, die Funktionen und \(\pi\) sind Bestandteil von numpy

t = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi)

plt.plot(t, np.sin(t))

#plt.plot(t, np.sin(t), 'r--')

#plt.plot(t, np.sin(t), 'go')

Tabelle mit allen Farben und Styles: matplotlib.axes.Axes.plot

Neue Grenzen mit xlim(a, b) und ylim(a, b)

plt.plot(t, np.sin(t))

plt.xlim(0, 2 * np.pi)

plt.ylim(-1.2, 1.2)

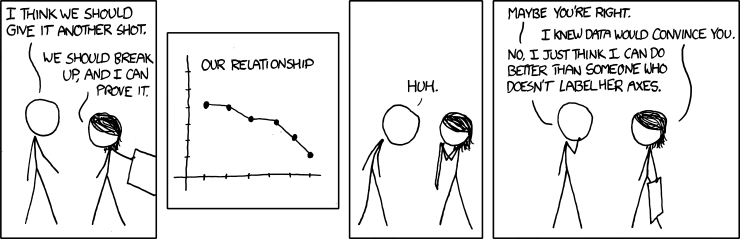

Es fehlt noch etwas...

XKCD comic on why you should label your axes.

with plt.xkcd():

plt.plot(t, np.sin(t))

plt.xlabel('t')

plt.ylabel('sin(t)')

plt.ylim(-1.1, 1.1)

plt.xlim(0, 2*np.pi)

Achsen-Beschriftungen können mit LaTeX-Code erstellt werden → LaTeX-Kurs in der nächsten Woche.

plt.plot(t, np.sin(t))

plt.xlabel('$t$')

plt.ylabel(r'$\sin(t)$')

Legenden für Objekte die ein label tragen

plt.plot(t, np.sin(t), label=r'$\sin(t)$')

plt.legend()

#plt.legend(loc='lower left')

#plt.legend(loc='best')

Mit grid() wird ein Gitter erstellt:

plt.plot(t, np.sin(t))

plt.grid()

Laden von Daten

x, y = np.genfromtxt('example_data.txt', unpack=True) # unpack=True falls Daten spaltenweise angeordnet sind

plt.plot(x, y, 'k.')

t = np.linspace(0, 10)

plt.plot(t, 5 * t, 'r-')

Auslagern in ein Skript

Speichert den folgenden Code in eine Textdatei plot.py ab.

Öffnet ein Terminal und startet das Programm:

python plot.pyimport matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

x = np.linspace(0, 1)

plt.plot(x, x**2, 'b-')

plt.savefig('plot.pdf')

Mit savefig speichert man die Abbildung.

In diesem Fall sollte die Datei plot.pdf erstellt worden sein.

Es gibt viele Ausgabeformate: pdf, png, svg, LaTeX

Komplexere Abbildungen

Natürlich kann man mehrere Linien in einen Plot packen:

x = np.linspace(0, 1)

plt.plot(x, x**2, label='$x^2$')

plt.plot(x, x**4)

plt.plot(x, x**6, 'o', label='$x^6$')

plt.legend(loc='best')

Es werden nur die Plots in der Legende angezeigt, die ein Label haben.

Man kann auch mehrere Plots in ein Bild packen:

x = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi)

# Anzahl Zeile, Anzahl Spalten, Nummer des Plots

plt.subplot(2, 1, 1)

plt.plot(x, x**2)

plt.xlim(0, 2 * np.pi)

plt.subplot(2, 1, 2)

plt.plot(x, np.sin(x))

plt.xlim(0, 2 * np.pi)

Dies führt manchmal zu Spacing-Problemen und Teilen die sich überscheneiden, Lösung: plt.tight_layout()

x = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi)

# Anzahl Zeile, Anzahl Spalten, Nummer des Plots

plt.subplot(2, 1, 1)

plt.plot(x, x**2)

plt.xlim(0, 2 * np.pi)

plt.title("$f(x)=x^2$")

plt.subplot(2, 1, 2)

plt.plot(x, np.sin(x))

plt.xlim(0, 2 * np.pi)

plt.title("$f(x)=\sin(x)$")

plt.tight_layout()

Plot im Plot:

plt.plot(x, x**2)

# Koordinaten relativ zum Plot (0,0) links unten (1,1) rechts oben

plt.axes([0.2, 0.45, 0.3, 0.3])

plt.plot(x, x**3)

Plots mit Fehlerbalken

Sehr häufig werden im Praktikum Plots mit Fehlerbalken benötigt:

x = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi, 10)

errX = 0.4 * np.random.randn(10)

errY = 0.4 * np.random.randn(10)

plt.errorbar(x + errX, x + errY, xerr=0.4, yerr=0.4, fmt='o')

Achsen-Skalierung

Logarithmische (und auch viele andere) Skalierung der Achsen ist auch möglich:

x = np.linspace(0, 10)

plt.plot(x, np.exp(-x))

plt.yscale('log')

#plt.xscale('log')

Polar-Plot

Manchmal braucht man einen Polarplot:

r = np.linspace(0, 10, 1000)

#r = np.linspace(0, 10, 50)

theta = 2 * np.pi * r

plt.polar(theta, r)

Ticks

Man kann sehr viele Sachen mit Ticks machen…

x = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi)

plt.plot(x, np.sin(x))

plt.xlim(0, 2 * np.pi)

# erste Liste: Tick-Positionen, zweite Liste: Tick-Beschriftung

plt.xticks([0, np.pi / 2, np.pi, 3 * np.pi / 2, 2 * np.pi],

[r"$0$", r"$\frac{\tau}{4}$", r"$\frac{\tau}{2}$", r"$\frac{3\tau}{4}$", r"$\tau$"])

plt.title(r"$\tau$ FTW!")

months = ['January',

'February',

'March',

'April',

'May',

'June',

'July',

'August',

'September',

'October',

'November',

'December']

plt.plot(np.arange(12), np.random.rand(12))

plt.xticks(np.arange(12), months, rotation=45, rotation_mode='anchor', ha='right', va='top')

plt.xlim(0, 11)

Histogramme

Sehr häufig braucht man Histogramme.

# Zufallsdaten generieren:

x = np.random.normal(0, 1, 1000)

plt.hist(x)

Anzahl der Bins und den Bereich festlegen:

plt.hist(x, bins=20, range=[-3,3])

Möchte man mehre Datensets unterschiedlicher Größe vergleichen, muss man normieren und das gleiche "Binning" wählen.

y = np.random.normal(0, 1, 100)

plt.hist(x, bins=20, range=[-3,3], normed=True)

plt.hist(y, bins=20, range=[-3,3], normed=True)

geht noch schöner:

y = np.random.normal(0, 1, 100)

plt.hist(x, bins=20, range=[-3,3], normed=True, histtype='step')

plt.hist(y, bins=20, range=[-3,3], normed=True, histtype='step')

Objektorientiertes Plotten

Bis jetzt haben wir die schnelle Variante mit der pyplot-Syntax benutzt. Wenn man viele Plots anlegt, ist der objekt-orientierte Ansatz für matplotlib besser geeignet.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

t = np.linspace(0, 2*np.pi, 1000)

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(2, 1)

ax1.plot(t, np.sin(t), 'r-')

ax1.set_title(r"$f(t)=\sin(t)$")

ax1.set_xlabel("$t$")

ax1.set_xlim(0, 2 * np.pi)

ax1.set_ylim(-1.1, 1.1)

ax2.plot(t, np.cos(t), 'b-')

ax2.set_title(r"$f(t)=\cos(t)$")

ax2.set_xlabel("$t$")

ax2.set_xlim(0, 2 * np.pi)

ax2.set_ylim(-1.1, 1.1)

fig.tight_layout()